Tax Brackets and Rates: 1913-2024

Beyond Top Marginal Rates: Uncovering a More Accurate History of U.S. Income Taxes by Jointly Presenting Brackets, Rates, and Inflation.

A common element of U.S. income tax history discussions is the inclusion of a graph showing top marginal tax rates over time.1 The frequency with which such graphs are presented is somewhat perplexing since it implies a broader relevance than is warranted. The top marginal rates have always applied to only a very small fraction of the taxpaying population, thus a graphical rendering of their history has limited direct informational value to the majority of individuals who, not having top incomes, will never personally encounter top marginal rates.

A potentially more significant, and frequently overlooked, aspect of tax history is the historical evolution of tax bracket thresholds and their interplay with economic factors. Adjustments to these brackets, particularly when analyzed in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, can have an impact on taxpayer liability equivalent to, or even greater than, changes in statutory rates. Even when bracket thresholds and rates appear to be stable from year to year, inflation can lead to 'bracket creep,' effectively increasing an individual's real tax burden as nominal income growth pushes them into higher tax brackets. During periods of inflation, stable tax policy is essentially a policy of constant tax increases.

Presenting historical tax brackets in nominal dollars, rather than their equivalent worth today (real dollars), can make it genuinely challenging for most people to understand their true historical impact.

Consider this common scenario: An individual today might be aware that the top federal income tax rate in 2024 applied to incomes exceeding roughly $609,350. If they then learn that in 1913, the first year of our modern income tax system, the top rate was levied on incomes over $500,000, their initial reaction might be that the thresholds aren't dramatically different. However, their perspective on historical policy shifts would likely change significantly upon discovering that $500,000 in 1913 had the purchasing power of about $16 million in 2024 dollars. The 2024 top bracket threshold, rather than being about 20% higher than the 1913’s, is actually only about 4% of 1913’s threshold. Today’s reader might also be surprised to discover that in several past years, the top marginal rate only applied to incomes that were greater than $100 million in today’s dollars!

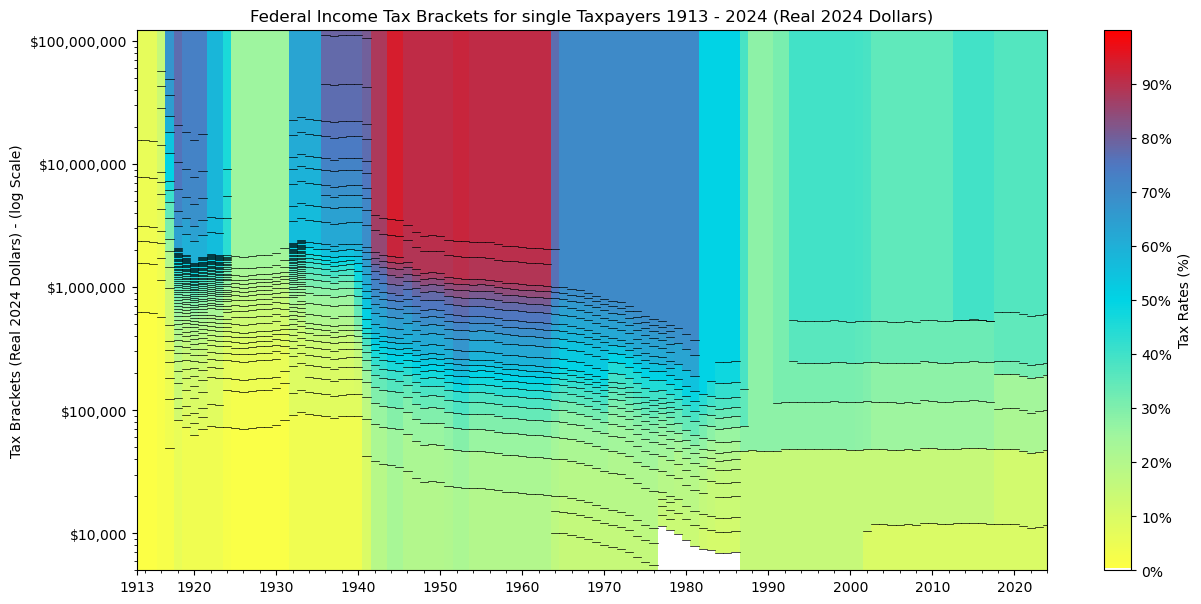

Unfortunately, presenting both brackets and rates in a single chart is difficult. Nonetheless, I’ve attempted to produce such a chart which you’ll find below with some explanation following.2

In the chart, whose y-axis has a log scale, the brackets for each year (as many as 56) are shown by horizontal black lines and the tax rate for each bracket is indicated by its color, according to the legend on the right.

Low-End Taxes have remained low while Top Taxes have fallen dramatically

What should be immediately apparent is that the tax rates that have applied to single filers with incomes similar to today’s median income, about $57,000, have not changed dramatically over time. What has changed is that taxes on wealthier filers have dropped dramatically. While those with annual incomes greater than $1 million once paid much higher taxes than others, and those with incomes of $10 million or $100 million paid even higher taxes, today everyone with an income over $609,350 pays a rate once only paid by those with much, much lower incomes.

Bracket-Creep is quite visible

The chart above shows the effect inflation once had on real bracket thresholds. As can be seen by comparing that inflation-adjusted chart to the un-adjusted chart below, it is clear that even when nominal dollar brackets didn’t change, “Bracket-Creep” due to inflation tended to drive brackets constantly lower from year to year between 1940 and 1985. During those years, even if one’s real income was stable, the applicable tax rate grew over time due to inflation. Since 1985, the bracket thresholds have been annually adjusted for inflation.

War-time once led to higher taxes

During the periods corresponding to World War I (late 1910s) and especially World War II (early-mid 1940s) rates increased dramatically across many income levels and so did the number of brackets. The high WWII rates persisted until the tax cuts proposed by President Kennedy were adopted in the Revenue Act of 1964.

The sheer complexity of the mid-century system is striking

The density of lines and color gradations from roughly the 1940s to the 1960s visually screams "complexity!" This wasn't just about high top rates; it was about a highly articulated system of brackets with many small steps. Given this complexity, it isn’t surprising that tax simplification became a recurring political theme.

Periods of extreme volatility vs. relative stability in tax structure:

The graph highlights distinct eras of tax policy. The period from the 1930s through the 1970s appears particularly turbulent in terms of both rates (color shifts) and bracket structures (lines moving). The early years (1913-1920s) also show rapid changes. In contrast, the period from the late 1980s/early 1990s through to today appears much more stable in terms of both bracket and rate structure. Of course, this Post-Reagan era, reflects the impact of the Republican’s almost absolute refusal to consider tax increases as well as their focus on tax cuts, particularly for the wealthy, whether or not there is any evidence that such tax cuts will either generate increased revenue or be offset by spending cuts. The result of this refusal to raise taxes, codified via the Taxpayer Protection Pledge, has resulted in a rapid increase in the national debt — a harbinger of future tax increases.

While I believe that the chart above more clearly illustrates key aspects of income tax history than do others I have found, I recognize that it is a bit of a mess — and may be challenging for the color blind... It is useful to compress a great deal of information in a single image, but sometimes, one can go too far. Thus, I’m hoping that if anyone knows of a more effective presentation of this information that they will let me know of it.

I haven’t found much evidence of previous attempts to display the history of both brackets and rates in a single image while also considering the impact of inflation. I’ve also found very little evidence of detailed academic studies that present the history of brackets. Almost all the studies I have found, other than a few that analyze the Bracket-Creep problem, are focused almost exclusively on rates, not on brackets. However, one study that I have found to be very useful was: Tracey M. Roberts’s 2014 article, Brackets: A Historical Perspective.3 If this subject interests you, I think you’ll find Roberts’s discussion worth the time to read.

Let me know in the comments if this presentation is at all useful to you. Also, please use the comments to make any suggestions for improving the chart above, or for an alternative, superior presentation.

Catherine Mulbrandon, at Visualizing Economics, has produced a particularly pleasing, although out-of-date, graph of Top Marginal Tax Rates: 1916-2012. Unfortunately, it provides no insight into brackets.

The chart is based on Historical U.S. Federal Individual Income Tax Rates & Brackets, 1862-2021, published by The Tax Foundation. I’ve added data for 2022 - 2024 based on IRS publications.

Roberts, T. M. (2014). Brackets: A Historical Perspective. Northwestern University Law Review, 108(3), 34. Retrieved from https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=nulr

This is very interesting. Though I still stand by my suggestion to try and make the graph three dimensional. Regardless, I will continue to think about other ways to portray this information.

The chart is a little bit confusing to me. Seems to me like there are several takeaways. One is that inflation-adjusted tax brackets are shifting down, thus covering more people at the top. On the other hand, tax rates on the wealthy are also declining. It's not clear to me what the net effect of all this is from your charts.